Wednesday, 25 July 2012

Tuesday, 24 July 2012

Regions where water disputes are fuelling tensionsنزاع محتمل بين العراق وسوريا وتركيا وإيران على مصادر دجلة والفرات

Regions

where water disputes are fuelling tensions

نزاع

محتمل بين العراق وسوريا وتركيا وإيران على مصادر دجلة والفرات

Mon, Jul 23 2012

Disputes over water are common around the world, exacerbated

by climate change, growing populations, rapid urbanisation, increased

irrigation and a rising demand for alternative energy sources such as

hydroelectricity.

ذكرت وكالة رويترز في تقريرها أن هناك احتمال نزاع قائم على

المياه في جنوب آسيا عام 2050 بسبب استمرار النمو السكاني وتزايد الضغوط على

إمدادات المصادر الطبيعية والتغيرات الحاصلة في المناخ العالمي ولا يقتصر الأمر

على جنوب آسيا فقط بل يبدو أن النزاع على المياه سيغدو ظاهرة عالمية .

وأشار التقرير إلى أن" هناك

نزاعا سيتصاعد بين العراق وسوريا وتركيا وإيران على مصادر نهري دجلة والفرات كما

أن المشكلة أيضا ستتفاقم حول نهر ألأردن المنقسم بين الأردن وإسرائيل وهناك عشر

دول افريقية تتقاسم جسد نهر النيل. وكانت وكالة المخابرات المركزية الأمريكية قد

حذرت في تقريرها الصادر في شباط الماضي من أن إمدادات المياه العذبة في العالم سوف

لا تلبي الطلب عليها بحلول عام 2040 وهو ما يزيد من حالة عدم الاستقرار السياسي

وإعاقة نمو الاقتصاد العالمي وتعريض اسواق الغذاء العالمي للخطر

Following are a few of the regions where competition for

water from major rivers systems is fuelling tension.

Iraq, struggling with water shortages due to aridity and

years of drought, says hydroelectric dams and irrigation in Turkey, Iran and

Syria have reduced the water flow in both rivers.

Increasing desertification, especially in Iraq, is

compounding problems. A large amount of Euphrates' waters evaporate due to extreme

heat. Contamination from pesticides, discharge of untreated sewage and excess

salinity due to low water levels are all common.

Iraq, Syria and Iran want more equitable access and control

from Turkey, where almost 98 percent of Euphrates waters originate. Despite

some cooperation on common management, a final agreement has yet to be reached.

NILE BASIN

The countries of the Nile basin are Egypt, Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Uganda, Kenya, Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi, Rwanda and Tanzania.

Egypt and Sudan control more than 90 percent of the Nile's

waters due to colonial-era and other treaties but others in the basin want a bigger

share.

Demand for irrigation has risen, with millions of hectares

leased for large-scale farming. Dams have complicated access to water.

Water needs are expected to rise as the Nile basin

population is projected to reach 654 million by 2030, up from 372 million in

2005, according to UN estimates.

JORDAN RIVER BASIN

The river basin is highly stressed due to aridity in Jordan, Israel and Palestinian Territories.

All three discharge untreated or poorly treated sewage. The

Mountain Aquifer - a key fresh water source for West Bank Palestinians and

major Israeli cities - is threatened by decades of over-exploitation and

groundwater pollution.

Despite efforts to cooperate, agreements to share water

resources are complicated by the long-stalled Middle East peace process. Israel

dominates the Palestinian water economy.

CENTRAL ASIA

Central Asia is one of the world's driest places, where, thanks to 70 years of Soviet planning, growing thirsty crops such as cotton and grain remain the main source of income for most people.

Disputes over water use from the Syr Daria and Amu Daria

rivers have increased since independence in 1991. Problems are compounded by

rising nationalism and lack of progress on a regional approach to replace

Soviet-era systems of water management.

Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan need more water for

growing populations and farming, while economically weaker Kyrgyzstan and

Tajikistan want more control for hydropower and irrigation.

Afghanistan, linked to Central Asia by the Amu Daria, is

claiming its own share of the water.

India and Pakistan are both building hydropower dams in

disputed Kashmir along Kishanganga river. Pakistan fears India's dams will

disrupt water flows.

India, for its part, is concerned that China is building

dams along the Tsangpo river, which runs into India as the Brahmaputra.

MEKONG RIVER BASIN

Most Mekong countries, especially China, have been planning and building hydropower dams since the late 1980s.

Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam argue that China

diverts or stores more than its fair share of water due to dam-building on the

Upper Mekong.

There is growing concern about serious environmental damage

to agriculture, fisheries and food security for some 60 million people due to

plans by Laos and Cambodia to build more than 10 dams along the Lower Mekong.

Despite cooperation efforts by Cambodia, Thailand, Laos and

Vietnam through the Mekong River Commission, national interests are getting in

the way of joint river management.

Sources: Reuters, AlertNet, Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, Brookings Institute, International Crisis Group, Nile Basin Research Programme, GRAIN, UNDP

Sunday, 22 July 2012

Iraq struggles to reform 'inefficient' rationingالعراق يصرف 5 مليارات دولار سنويا على مفردات الحصه الغذائيه

BBC News, 21.7.2012

|

| اكثرية الخضار والفواكه هي الاخرى مستورده |

Iraq spends around $5bn (£3.18bn) annually to distribute food to

its population.

On the western bank of

the Tigris in north Baghdad stands a rare relic of British rule in Iraq - a

silo built during World War II to feed British soldiers.

Right next to it

stands a taller structure, built in 1962 by the Soviet Union, as Iraq flirted

briefly with communism.

Several trucks stacked

with bags of rice and wheat drive past to empty their loads, and all around

flocks of pigeons chase after fallen grain.

The site belongs to

the state-owned Grain Board of Iraq, which imports rice and wheat for distribution

to the population.

About 12,000 tonnes of

wheat are stored here - a fraction of the quarter of a million tonnes Iraq

imports every month.

And the vast majority

of Iraqis receive their share almost for free.

For more than two

decades, the Iraqi government has administered a massive public distribution

system, under which all citizens are entitled to receive essential items for

only symbolic payment.

The Iraqi government

says it wants to reform the system, but its efforts have run into difficulties.

Fears

for future

The system was put in

place after the UN Security Council imposed sanctions on Iraq following its

invasion of Kuwait in 1990.

More than nine years

after the sanctions regime was lifted, Iraq still spends around $5bn (£3.18bn)

a year to distribute food to its population.

The items include

sugar, cooking oil, and baby milk formula for families with infants. The Grain

Board is responsible for rice and wheat, which is then made into flour before

being handed out.

"We deal with

more than three million tonnes of wheat every year," a press officer at

the Grain Board told me proudly.

But some of it seems

to be going to waste. Every citizen is entitled to 9kg (20lbs) of wheat a

month, and many people are not even claiming their share.

Hasan Ismail, the

director general of the Iraqi Grain Board, admitted there was a problem.

"Sometimes the

market does get saturated, especially with flour, because in cities people no

longer make their own bread. But people in the countryside consume all of their

rations, and they need them."

In distribution

centres, few complain about waste or abundance.

Daoud is a

construction worker in central Baghdad, and he's come to collect his monthly

share from the local distribution agent. "It's getting

less and less, year by year, and there's no variety. We get cooking oil,

sometimes rice, and flour. No tea, no washing powder, and no salt."

Daoud fears that the

distribution system is gradually fading away. "The whole thing

will be finished soon, and we better get used to it."

Means

testing

The government insists

it has no plans to end the system, only to introduce gradual reforms.

It says that those

with monthly incomes of more than 1.5m Iraqi dinars ($1,200; £764) are not

entitled to receive it any more.

But Mr Ismael says the

attempt to implement the new measure has already run into trouble. "It's not easy at

the moment in Iraq to track people's incomes. The government lacks databases of

people's incomes, and we can only track the incomes of those in the public

sector."

"There could be

some who work in the private sector with incomes of over 10 million Iraqi

dinars a month who still receive their share."

Tracking incomes could

be the least of the government's difficulties.

Like most subsidy

programmes all over the world, the system is politically difficult to reform,

and most politicians steer clear of pressing the issue

Despite allegations of

corruption and inefficiency, the public distribution system has been credited

with achieving food security for a large segment of the Iraqi population during

the past two decades.

Today 23% of Iraqis

live below the poverty line, and remain in desperate need of government

support. The challenge facing

the government is to strike the right balance between encouraging productivity

and less reliance on the state, while making sure not to jeopardise the food

security of those most in need.

Saturday, 21 July 2012

Monday, 9 July 2012

Sunday, 8 July 2012

Saturday, 7 July 2012

FOOT AND MOUTH DISEASE - MIDDLE EAST: EGYPT, SEROTYPE SAT-2,

|

| الحُمّى القلاعية |

;http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn22016-footandmouth-disease-stalks-egypt.html;

Date: Thu 5 Jul 012

Date: Thu 5 Jul 012

A new strain of foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) in Egypt could aggravate discontent among the rural poor and prolong the country's political turmoil.

As Egypt struggles to make a vaccine, agriculture experts fear a vicious circle has begun: political disarray helps spread animal disease, which deepens poverty and discontent -- and breeds more political disarray. Meanwhile neighbouring countries fear Egypt's virus could soon reach them.

FMD kills young cattle, buffalo, and other ruminants, weakens older

ones and slashes farms' productivity. At a meeting in Bangkok,

Thailand, last week, the member countries of the UN Food and

Agriculture Organization (FAO) launched a plan to get FMD under

control worldwide by 2027 [see 20120628.1184291]. Yet the FAO cannot

get money to have vaccine made out of existing stocks of ingredients

for the Egyptian outbreak.

Egypt already harbours 2 strains of the FMD virus [serotypes O and A],

but its livestock have some resistance to them, through either

exposure or vaccination. They have none to the new strain, SAT2.

In February [2012], migrant herders also brought SAT2 to Libya,

although there are slight genetic differences between the viruses in

Libya and Egypt. Political upheaval in both countries means "the

ability to do the right surveillance and control has been quite

diminished," says Juan Lubroth, head of animal health at the FAO in

Rome. He fears what could also happen if the virus turns up in Syria

or Iraq.

That puts the whole region at risk: FMD is the most contagious animal

virus known. European Union officials are said to be preparing

contingency plans. Israel has vaccinated livestock along its southern

border and given vaccine to Palestinian authorities, who have

contained the virus after infected animals came to Gaza through

smuggling tunnels from Egypt.

Sunday, 1 July 2012

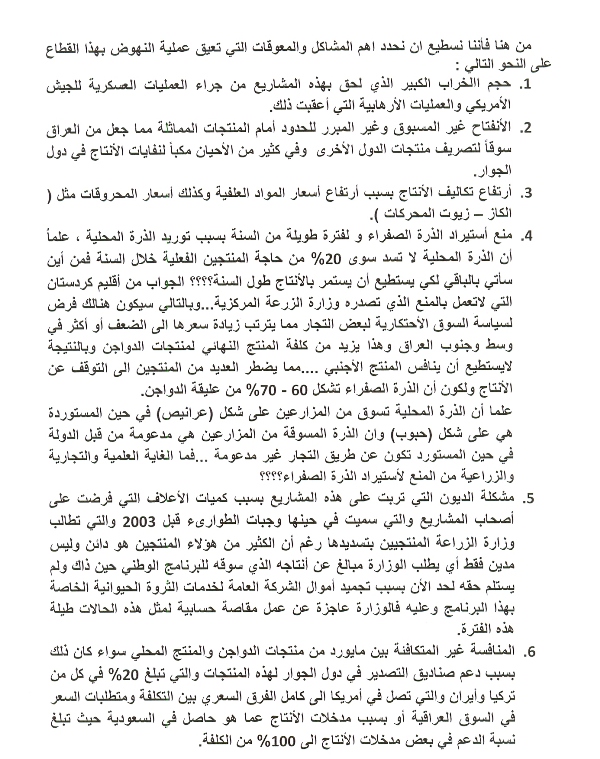

THE RICE OF THE PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM (PDS)نوعيه رز الحصه التموينيه

|

| The rice on the left(رز تجاري) of the picture is commercially sold rice while the rice on the right is PDS(رز الحصه التموينيه) |

The Oil for Food Program that commenced in 1996 and under its

offices the Public Distribution System (PDS) System was set up to distribute

rice, oil, milk powder etc and this still continues. The rice in the right of

the picture above is a sample of the rice distributed through parastatal

outlets(المبايعه) that charge the recipients 500 ID for

receiving the monthly handout for each family member. Initially these food

handouts were of great benefit to people as the standard of living was poor

however, over the last 7 to 8 years people’s incomes and living standards have

markedly improved, even when electricity cuts and poor health standards are

taken into account, and both the quantity and the quality of the foods

distributed have deteriorated. The food distributed under the program is

imported from many places and since 2003 there have been reports of numerous

scandals with regard to these imports.

Under the IPD system every Iraqi over 1 year of age is entitled to

3 kg of rice per month but some months they do not receive their rice ration

and this is then lost to them. The quality of the rice is so poor that often

they will sell it back to the outlet manager at the price of 50 ID per kilo and

the money is deducted from the 500

ID /per person charge they must

pay the manager for receiving their monthly quota of food under the IPD system .The

people sell this inferior quality rice

to street traders or outlet managers (المبايعه)for 50 ID per kilo.

The rice to the left of the picture is a better quality rice,

(Ahmed rice), that can be bought in the market place for 2500 ID per kilo, or

the cost of 50 kilos of government rice. One can easily see the difference

between the two cereals with the rice distributed by the program being of

poorer quality and badly threshed as many grains are still in the husk. Over 20

years ago, when I and my family lived in Moghadishu-Somalia,

this poor quality rice was often all that was available to us but there are now

some 40 varieties of good quality, basmati rice available on the open market

here in Iraq. It is no surprise that these better quality grains are used in

preference to the hand out grain but what happens to the rice that is sold back

to the outlet managers and street traders? I have been told that it ends up as

animal or bird feed or that it may be taken out of the country and is then

imported back in to be redistributed through the network.

Whatever the rice is used for the main concern is that in the more

affluent society of today these handouts

to every Iraqi are no longer required and the program should be gradually wound

down. The logistics and distribution costs of the PDS could be put to

better use now but it will take a strong political force to replace these

distributions with something else.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)